Rachel Falcone and Michael Premo: Housing is a Human Right

A Brooklyn resident at a rally for tenant and housing rights. © Michael Premo, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

Everyone can relate to the need for a home, and so it’s a starting place in which to then have a conversation about what we want our communities to look like—where we actually see each other as human beings and not just as numbers, cost, and something for profit. — Rachel Falcone

BY DIANE BEZUCHA | STUDENT CONTRIBUTOR| THE UNSHELTERED ISSUE | WINTER 2017

“You push the ant in the sink and turn the water on and you watch the ants struggle to get out of this water… it’s swirling down the drain. I always said homelessness was like that: here comes the water on you and eventually you’re going to go down the drain unless something or somebody pulls you out.” – Rob Robinson

Rob Robinson was a college graduate with a good job and a 401(k) until his employer downsized. In this 2009 recorded interview, he describes his own sudden transition from stability to homelessness. In March of 2001, Robinson was offered a new position in his company, so he picked up and moved his life from Long Island, New York to Miami, Florida.

•Housing is a Human Right Storytelling Project Volume 1

•NYC Tenant Rights FAQ

•Housing Rights NY organization

•“In New York, Having a Job, or 2, Doesn’t Mean You Have a Home” (NY Times)

By July his employer had run out of money and Robinson was laid off. He survived on unemployment for more than a year, but when that ran out, he was forced to use his savings and 401(k). Even when he lost his home and began sleeping in his car, he never believed he would become homeless. Eventually Rob found himself living on Miami Beach and panhandling in shopping centers just to afford to eat.

Rob’s story is not unique. The majority of people experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity are battling forces that are outside of their control. We are seeing this story play out across the United States, but in New York City it has reached new heights. For example: An elderly couple, married for 47 years, had been living in their Crown Heights, Brooklyn apartment for 20 years when their landlord asked them to temporarily move into another unit in the building so he could make some improvements.

What the landlord did instead was divide their two and a half-bedroom home into several smaller units that he rented out from under them at a higher price. The couple’s things were piled carelessly in the kitchen and basement, and the unit they had been forced into did not receive any of the updates provided to other units. In fact, the landlord ripped out their sink, cut holes in sewer pipes, and ran leaking PVC piping through the couple’s living space to service the new units upstairs. In an effort to drive the couple out, the landlord effectively made their home unlivable. The couple, in their mid-seventies with health conditions, were forced to find a new home.

A Crown Heights landlord allowed an elderly couple’s apartment to fall into disrepair in an effort to force the tenants out. © Michael Premo, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

These are just two of the stories collected by artists/filmmakers Rachel Falcone and Michael Premo as part of their oral storytelling project, Housing is a Human Right. The duo met when they were both working for StoryCorps—a nonprofit whose mission is to “preserve and share humanity’s stories”—around the time of the 2008 financial crisis. As they interviewed people across the United States, they noticed a recurring theme: the struggle for home.

“So much of what people were talking about was home and fragility around home,” says Falcone. “We were just fascinated by the through line. People were trying to obtain or maintain their home and that impacted the rest of their lives.”

Rachel Falcone interviewing a storyteller at her home. © Michael Premo, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

When the artists returned to New York City around 2009, they decided to continue to explore the struggle for housing in a more local context and began collecting stories from a diverse array of New York City residents. “We wanted to be able to spend three or four hours with people and really hear their truth,” says Falcone. “People are the experts and so if we’re going to really think about solutions to the housing crisis, it made sense to listen to the people that are dealing with it.”

The artists spoke with eleven storytellers, including the elderly couple being forced out of their home in Crown Heights, a woman who lost her home to foreclosure when she was diagnosed with cancer, and an older woman forced to live with roommates to make rent payments. Longer interviews are distilled to shorter clips, which are remixed with music and soundscapes. At the center of their stories are the questions: What does home mean? What does it mean to have a fragile home?

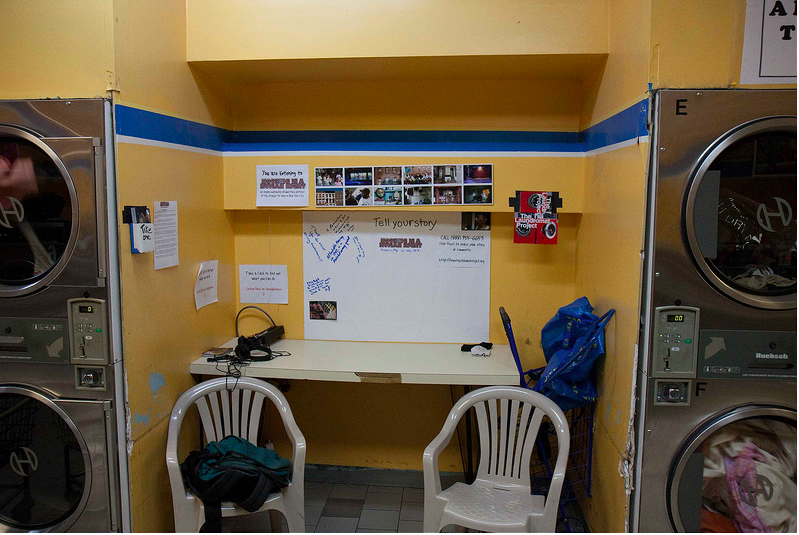

At the same time, Premo landed a residency with the Laundromat Project—an organization that places resident artists as community leaders in New York City neighborhoods—which served as a catalyst for their first exhibition in 2009. As the name suggests, the exhibit took place in a Fort Greene laundromat, where large color images were hung on the walls, depicting scenes from the stories they collected while their interviews and mixtapes played over the hum of washers and dryers. The artists, storytellers, and community residents all attended the opening, listening to each other’s stories, sharing in collective realizations, and even recording new stories in a booth in the back.

Most Housing is a Human Right exhibitions include a soundbooth so that attendees can record their own stories on the spot and participate in this public art project. © Michael Premo, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

Hanging images from Housing is a Human Right in a laundromat as part of their first public exhibition. © Michael Premo, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

The decision to share these personal stories in a communal space was an intentional one. At each Housing is a Human Right exhibit, stories are played out loud in community venues so they can be collectively experienced. “These stories [of struggles with housing] are so often felt in isolation,” says Falcone. “We think about our work in terms of how do we make this a performance that is collectively experienced—where people are both listening together and then talking together and really having a discussion.”

In a later iteration of the project called Sandy Storyline, which collected stories about the impact of Hurricane Sandy, the artists chose to exhibit stories in the round, so viewers were not only watching a video but also seeing the reactions on the person across from them. This emphasis on collectivity lies at the very heart of the project, which aims to challenge our notions of housing insecurity and homelessness as individual experiences of failure rather than systemic neglect.

Premo and Falcone have exhibited their Housing is a Human Right project in various cities and spaces. © Michael Premo, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

“The dominant narrative about housing very much others people in a way that says, this is exceptional that you’re homeless—you really did something wrong in order to go into foreclosure,” says Falcone. In reality, most people find themselves in a state of homelessness or housing insecurity as the result of a personal crisis, such as a sudden change in health, a layoff, or a natural disaster. Falcone continues: “There’s a lot of personal responsibility and there’s not a systemic responsibility around the fact that as a community, we failed this person.” The stories told in Housing is a Human Right challenge this assumption and build a counter-narrative around our collective need for home.

“Everyone can relate to the need for a home, and so it’s a starting place in which to then have a conversation about what we want our communities to look like—where we actually see each other as human beings and not just as numbers, cost, and something for profit.” In the tradition of social practice art, this community dialogue is as much a part of the artwork as the stories and images themselves. “We value process as much as the product,” says Falcone. “It’s super important that this is a restorative process for the people that are sharing and for the people that are listening.”

Rachel Falcone (left) interviews a storyteller. © Michael Premo, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

Falcone believes that their work is a form of Restorative Narrative—stories that focus on the resiliency of a community in the midst or aftermath of tragedy—but, like many people in that particular field of journalism, they constantly struggle to balance the tragic with the hopeful. “A lot of these stories are really sad and hard,” she notes, “but where’s the hope in some of the sadness? That’s often what we’re trying to convey. Where’s the lesson, or where’s the learning, or where’s the thing that they can offer someone else?”

For Falcone and Premo, that lesson is sometimes as simple as: you are not alone. The stories in Housing is a Human Right suggest that there is power in collectivizing our struggle.

“Movements sometimes are fighting against—fighting against evictions, fighting against these things one by one.” But what if, the artists ask us, we were building towards something—a collective narrative, a new paradigm? The goal of the project is not necessarily to change the individual circumstances of the storytellers themselves, but to help people see themselves as part of a larger narrative that changes how we view housing and homelessness as a society.

“The whole project is around saying, this is not your personal problem; this is about an issue that we actually all can relate to. If we all see that these are issues that affect all of us, and this is a systemic issue that we need to deal with as a society, then we can start to look at it differently,” she says.

Brooklyn residents rally for tenant and housing rights. © Michael Premo, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

As the project’s title suggests, the artists are using collective stories to reframe housing as a human right. “If we can help people get to that journey where they really understand and think that they have a right to housing, that’s a shift in mindset in which then we can look at policy through that lens,” says Falcone. “What would it mean to have a value-based system that actually supported people and housing as a human right? Would we think differently about evictions?”

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights currently recognizes 30 unique human rights, the right to “adequate living standard” among them, but not all of these rights are guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution. According to the nonprofit Advocates for Human Rights, this is because “economic, social, and cultural issues are not viewed as rights enjoyed by all [in the United States], public policies can exclude people from eligibility as long as they do not discriminate on prohibited grounds such as race. While ensuring that public policies are not discriminatory is important, it does not address the underlying problem of failing to guarantee for all people in the United States an adequate standard of living and other rights necessary to live in dignity.”

In 2010, Falcone and Premo took Housing is a Human Right to South Africa, where the right to housing is included in their post-apartheid constitution. In collecting stories there, the artists saw first-hand just how challenging it can be to actually implement housing as a human right, as they witnessed residents evicted in the wake of the FIFA World Cup. However, Falcone notes, “[South Africans] really believed in their right to housing in a way that I think many don’t yet feel the right to here.”

The experience confirmed the project’s premise that mindsets about housing and homelessness need to change before policies can. “Our goal has never necessarily been around policy. It’s about articulating what the human right to housing means to people, because art can create change on a spectrum; there is a spectrum of change the artist can play a role in. I’d love for it to change a policy maker, but I think the kinds of stories we tell are not directed at a specific policy change. They’re directed at articulating a different framework in which people can imagine the standard in which they could apply a policy.”

Since 2009, the project has iterated and evolved in numerous ways, including Sandy Storyline and, most recently, 28th Amendment, a portable exhibit and conversation series that imagines what would happen if we won the human right to housing in the United States. Falcone and Premo incorporated their multiple projects into the umbrella of Storyline Media in 2014 and are currently work on new projects, but according to the artists, “home will always be a through line.”

♦

DIANE BEZUCHA

Diane Bezucha grew up in Wisconsin and recently earned her Master’s in Art, Education, and Community Practice from New York University. She writes curriculum for the educational nonprofit BUILD and is also a photographer and aspiring photojournalist.

OF NOTE Magazine is free to readers, free of advertising, and free of subscriptions—all made possible by generous supporters like you. Your tax-deductible gift will help us continue to feature innovative and emerging global artists using the arts as tools for social change.

OF NOTE Magazine is a fiscally sponsored organization of the New York Foundation for the Arts, a 501 (c) (3), tax-exempt organization. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.